Christianity in Sichuan

Christianity is a minority religion in the southwestern Chinese province of Sichuan.[a] The Eastern Lipo, Kadu people and A-Hmao are ethnic groups present in the province.

History

[edit]East Syriac Christianity

[edit]

A presence of the East Syriac Christianity can be confirmed in Chengdu during the Tang dynasty (618–907),[1] and two monasteries have been located in Chengdu and Mount Omei.[2] A report by the 9th-century writer Li Deyu included in A Complete Collection of Tang-era Prose Literature states that a certain Daqin cleric proficient in ophthalmology was present in the Chengdu area.[3]

According to the 12th-century biji collection Loose Records from the Studio of Possible Change by Wu Zeng, during the Tang dynasty, "Hu" missionaries built a Daqin temple (i.e., an East Syriac church) into the existing ruins of the former Castle of Seven Treasures[b] at Chengdu, which was constructed by ancient Shu kings of the Kaiming dynasty (666 BC – 316 BC), with pearl curtains installed as decorative applications. It was later destroyed by the Great Fire of Shu Commandery during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (141 BC – 87 BC). The temple consisted of a gatehouse, halls and towers, just like the former castle, its doors were decorated with curtains made of gold, pearls and green jasper,[4] hence known as the Pearl Temple.[c][5]

According to a local tradition in Guanghan (Hanchow, lit. 'Han Prefecture'), its 8th-century prefect Fang Guan (Fang Kuan) was an East Syriac Christian. The tradition says that he worshipped the One God alone.[6] At his daily worship, Fang used to kneel on a stone which later came to be known as the Duke Fang Stone.[7] According to local testimonies, his name was carved on the no-longer-extant Nestorian stele at Wangxiangtai (Wang Hsiang T'ai) Temple.[8] The earlier name for the temple was Jingfu Yuan (Ching Fu Yuan), and Jingfu is a term with the meaning "Blessings of Christianity".[9]

The name Bakos, of a priest from Chongqing, is recorded on the left side, second row, at the very top of the "Nestorian" Xi'an Stele.[10] A pilgrim cross and several crosses of Syrian design were identified by a Syriac Orthodox priest Dale Albert Johnson in Ciqikou, Chongqing, dated to the 9th century. The pilgrim cross embedded in a stone on Ciqikou street has a simple style as the type carved by pilgrims and travelers.[11] Of the Syrian-designed crosses, one was found on the same street as the pilgrim cross, is fundamentally identical to crosses found in Aleppo, Syria.[12] The icon consists of a cross within a circle touching eight points. Two points on each end of the four ends of the cross touch the inner arch of the circle. Each arm of the cross is narrower near the middle than at the ends. The center of the cross draws to a circle at the center.[13] The rest are crosses within Bodhi leaves carved on a round granite stone base sitting in front of a curio shop on a side street in Ciqikou. According to Johnson, crosses within Bodhi leaves (heart shape or spade designs) are identified as Persian crosses associated with the Syrian Christians of India.[14]

According to David Crockett Graham, Marco Polo found East Syriac monasteries which still existed in Sichuan and Yunnan during the 13th century.[15]

Roman Catholicism

[edit]

The first Roman Catholic mission in Sichuan was carried out by the Jesuits Lodovico Buglio and Gabriel de Magalhães, during the 1640s. After the massacre of Sichuan by Zhang Xianzhong, a search for surviving Christians was carried out by Basil Xu, the then intendant of Eastern Sichuan Circuit, and his mother Candida Xu, who were both Catholics. They found a considerable number of converts in Baoning, Candida then invited the priest Claudius Motel to serve the congregation. Several churches were built in Chengdu, Baoning and Chongqing under the supervision of Motel.[16]

The predecessor of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Chengdu—the Apostolic Vicariate of Setchuen (Sichuan)—was established on 15 October 1696, and Artus de Lionne, a French missionary, was the first apostolic vicar.[17] In 1753, the Paris Foreign Missions Society took over responsibility for Catholic mission in Sichuan. In 1803, the first synod ever celebrated in China took place in Chongqingzhou, convened by Louis Gabriel Taurin Dufresse.[17][18][19] By 1804, the Sichuanese Catholic community included four French missionaries and eighteen local priests.[20] By 1870, the Church in Sichuan had 80,000 faithful, which was the largest number of Catholics in the entire country.[21]

On 27 March 1846, part of the western territory of the Apostolic Vicariate of Setchuen was split off to form the Apostolic Vicariate of Lhasa, which marked the beginning of the Paris Foreign Missions Society's Tibetan Mission.

The first group of Spanish Redemptorists left for China in February 1928: Segundo Miguel Rodríguez, José Morán Pan and Segundo Velasco Arina. They were active in the Apostolic Vicariate of Chengdu and the Apostolic Vicariate of Ningyuanfu in Xichang,[22]:15 and had a house and chapel built in Chengdu.[23] The last Spanish Redemptorists were expelled from China by the Communist government in 1952.[22]:15

The Sichuan Major Seminary was established in 1984 in Chengdu.[24] In 2000, Lucy Yi Zhenmei, a 19th-century virgin martyr from Mianzhou (now Mianyang), was canonised a saint by Pope John Paul II. Today, the Catholic population of the province is estimated at 250,000 persons.[25]

Protestantism

[edit]

In 1868, Griffith John of the London Missionary Society and Alexander Wylie of the British and Foreign Bible Society entered Sichuan as the first Protestant missionaries to take up work in that province. They travelled throughout Sichuan and reported the situation along the way to the headquarters of various missionary societies in Britain and missionaries in China, which opened the door for the entry of Protestantism into Sichuan.[26]

However, no other missionaries visited this province again until 1877, when Rev. John McCarthy of the China Inland Mission (CIM), after landing at Wanxian, travelled via Shunqing to Chongqing, where he arrived on 1 May. There he rented premises for other CIM missionaries to use as a base.[27][28]

In 1882, American Methodist Episcopal missionaries arrived in Chongqing (Chungking). Their early efforts encountered strong resistance and riots that led to the abandonment of the mission. It was not until 1889 that these Methodists came back and started the mission again.[29]

The year 1887 marks the arrival of the Anglican representatives of the CIM. William Cassels, already in holy orders; Arthur T. Polhill-Turner, was reading for orders when he volunteered for China; and Montagu Proctor-Beauchamp. All three were members of the Cambridge Seven.[30]

In 1888, the London Missionary Society began work in Sichuan, taking Chongqing as their center, a city in the east of the province. In addition, they had a large district to the south and southeast.[31]

The first American Baptist missionaries to reach the province were Rev. W. M. Upcraft and Rev. George Warner, who sailed in 1889. The journey required many weeks before their arrival in Suifu, where they established the first mission station.[32] Four more stations were established in Jiading (Kiating, 1894), Yazhou (Yachow, 1894), Ningyuan (1905), and Chengdu (Chengtu, 1909).[33]

Robert John and Mary Jane Davidson of Friends' Foreign Mission Association introduced Quakerism into Tongchuan (Tungchwan) in 1889. Within 19 years five monthly meetings were successively established in Chengdu, Chongqing, Tongchuan, Tongliang (Tungliang) and Suining.[34]

At the close of 1891, the Rev. James Heywood Horsburgh, along with Mrs. Horsburgh, Rev. O. M. Jackson, three laymen, and six single women missionaries, entered Sichuan as the first band of Church Missionary Society (CMS) missionaries to take up work in that province.[35] By 1894, CMS work had started in Mianzhou (Mienchow), Zhongba (Chungpa), Anhsien, Mianzhu (Mienchu) and Xindu (Sintu).[36] Their first church was founded in 1894 in Zhongba.[37]

In 1892, the Canadian Methodist Mission established missionary stations in Chengdu and Leshan.[38] A church and a hospital were subsequently built in Jinjiang District, Chengdu, which was the result of a team effort by O. L. Kilborn, V. C. Hart, G. E. Hartwell, D. W. Stevenson and others.[39] In 1910, the Canadian Mission took over Chongqing district from London Missionary Society.[40]

The Anglican Diocese of Szechwan was established in 1895, under the supervision of the Church of England. The foundation of the diocese was the result from the efforts of William Cassels, Arthur T. Polhill-Turner and Montagu Proctor-Beauchamp.[41] Cassels was consecrated as the first diocesan bishop in Westminster Abbey, in the same year.

In 1897, Cecil Polhill, also one of the Cambridge Seven, along with other four China Inland Mission missionaries, they established a missionary station in Dajianlu (Tatsienlu), Sichuanese Tibet, which paved the way for the future construction of the Gospel Church.[42][43]

The West China Union University was launched in 1910, in Chengdu. It was the product of a collective effort of four Protestant missionary boards: American Baptist Foreign Mission Society (American Baptist Churches USA), American Methodist Episcopal Mission (Methodist Episcopal Church), Friends' Foreign Mission Association (British Quakers) and Canadian Methodist Mission (Methodist Church of Canada).[44] The Church Missionary Society (Church of England) became a partner in the university in 1918.[45][46]

In 1914, the Adventist Mission established a mission station in Chongqing. Their Sichuan Mission was officially formed in 1917.[47] In 1919, the mission was divided into East Sichuan Mission and West Sichuan Mission for easier administration.[48][49] The extreme west region was designated the Tibetan Mission headquartered at Tachienlu.[47]

By 1922, the Foreign Christian Missionary Society had its center at the Tibetan county of Bathang. Due to the constitution of Sichuan at the time, Bathang fell outside the western boundary and belonged to the special territory of Xikang (Chwanpien).[50]

Lutheranism also had a small presence in Chongqing, which was part of east Sichuan. The Lutheran Holy Cross Church was founded in Wan County in 1925, under the supervision of George Oliver Lillegard,[51] a pastor-missionary sent by the Lutheran Church – Missouri Synod.[22]

In 1940, the Church of Christ in China established the first mission station in Lifan, a county lying in the Sichuan-Khams Tibetan border region, as part of their Border Service Movement. This movement had a marked character of Social Gospel, with the aim of spreading Christianity to the Tibetan, Qiang and Yi peoples.[52]

In 1950 it was estimated there were more than 50,000 Protestants in Sichuan, meeting in hundreds of churches and chapels.[53] Today, the number of Protestants exceeds 200,000—many Christians reside in rural areas.[53] Panzhihua was an area of rapid growth of Christianity in around 2000.[53] A Sichuan Theological College exists.

Current situation

[edit]After the communist takeover of China in 1949, Protestant churches in the country were forced to sever their ties with respective overseas churches, which has thus led to the merging of all the denominations into the communist-sanctioned Three-Self Patriotic Church.[54]

As for the Catholic Church in China, all legal worship has to be conducted in government-approved churches belonging to the Catholic Patriotic Association, which does not accept the primacy of the Roman pontiff.[55]

Some missionaries were arrested and sent to "thought reform centers" in which they underwent disturbing re-education process in a vindictive prison setting.[56]

On 20 June 2009, the police in Langzhong set free 18 house church leaders arrested on 9 June.[57]

In 2018, Wang Yi, a well-known pastor from Chengdu and founder of the Early Rain Covenant Church, along with 100 Christians, was detained by authorities. Wang was reportedly arrested on allegations of "inciting subversion of state power".[58] That same year, four Christian churches in Sichuan were given an ultimatum and told they must join the Three-Self Church or be shut down.[59]

In 2019, 200 congregants in Chengdu began to meet in secret after their state-registered Three-Self church had been shut down.[60]

On 14 August 2022, police in Chengdu raided a Sunday gathering of the Early Rain Covenant Church and detained a leader.[61]

Eastern Orthodoxy

[edit]A tiny Eastern Orthodox community in Chengdu is supported by the United States-based Orthodox Christian Mission Center.[62] In 2019, Pravoslavie reported on a convert to Russian Orthodoxy, also from Chengdu.[63]

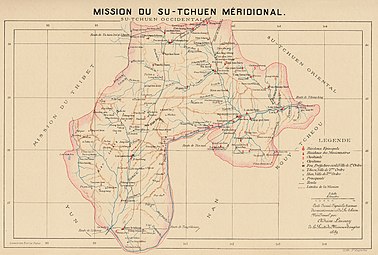

Maps

[edit]-

Seven apostolic vicariates of Sichuan (Catholic)

-

MEP Western Szechwan mission (Catholic)

-

MEP Eastern Szechwan mission (Catholic)

-

MEP Southern Szechwan mission (Catholic)

-

Map of Sichuan showing Anglican mission stations of China Inland Mission (CIM), Church Missionary Society (CMS) and Bible Churchmen's Missionary Society (BCMS)

-

Canadian Methodist Mission in central Sichuan

-

West China Mission of the United Church of Canada (Methodist)

-

American Methodist Episcopal Mission area in Sichuan

-

Map of Sichuan showing American Baptist mission stations

-

Area of Sichuan compared with British Isles. Shaded portion is Friends' Foreign Mission Association's district.

-

Friends' Foreign Mission Association's (Quaker) district in Sichuan

See also

[edit]- Christianity in Mianyang

- Islam in Sichuan

- An Account of the Entry of the Catholic Religion into Sichuan

- Anti-Christian Movement (China)

- Anti-missionary riots in China

- Antireligious campaigns of the Chinese Communist Party

- Chinese Rites controversy

- Denunciation Movement

- Khara-Khoto Christian manuscripts

- Underground church

- Category:Catholic Church in Sichuan

- Category:Protestantism in Sichuan

- Christianity in Sichuan's neighbouring provinces

Notes

[edit]- ^ Formerly romanized as Szechwan or Szechuan; also referred to as "West China" or "Western China".

- ^ Castle of Seven Treasures (traditional Chinese: 七寶樓; simplified Chinese: 七宝楼; pinyin: Qībǎo lóu; Sichuanese romanization: Ts'ie5 Pao3 Leo2)

- ^ Pearl Temple (traditional Chinese: 珍珠樓; simplified Chinese: 珍珠楼; archaic form: 眞珠樓 or 真珠樓; pinyin: Zhēnzhū lóu; Sichuanese romanization: Chen1 Chu1 Leo2)

References

[edit]- ^ Li & Winkler 2016, p. 261.

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (2016). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity (New ed.). London: I.B. Tauris. p. 183. ISBN 978-1-78453-683-1.

- ^ Kotyk, Jeffrey. "DDB: Nestorian Christianity in China". academia.edu. Retrieved 26 July 2022.

- ^ Wu, Zeng (1843). Nenggai zhai manlu (in Traditional Chinese).

- ^ Wongso, Peter (1 May 2006). 認識基督教史略: 二千年教會史簡介 [A Concise Illustration to History of Christianity] (in Traditional Chinese). Hong Kong: Golden Lampstand Publishing Society. p. 216. ISBN 9789627597469.

- ^ Drake, F. S. (1937). "Nestorian Monasteries of the T'ang Dynasty: And the Site of the Discovery of the Nestorian Tablet". Monumenta Serica. 2 (2): 293–340. JSTOR 40702954.

- ^ Donnithorne 1933–1934, p. 211.

- ^ Donnithorne 1933–1934, p. 212.

- ^ Donnithorne 1933–1934, pp. 215–216.

- ^ Li & Winkler 2016, p. 42.

- ^ Johnson, Dale A. (2012). "Did the Syriac Orthodox Build Churches in China?". soc-wus.org. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ^ Li & Winkler 2016, p. 44.

- ^ Li & Winkler 2016, p. 43.

- ^ Li & Winkler 2016, p. 48.

- ^ Graham, David Crockett (1 November 1961). Folk Religion in Southwest China (PDF). Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections (vol. 142, No. 2). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. p. 63.

- ^ Gourdon 1981, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b Charbonnier, Jean. "Partir en mission 'à la Chine' — Place aux prêtres chinois". mepasie.org (in French). Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 1 July 2011.

- ^ Wright, Arnold, ed. (1908). Twentieth Century Impressions of Hongkong, Shanghai, and other Treaty Ports of China: Their History, People, Commerce, Industries, and Resources. London: Lloyd's Greater Britain publishing Company.

- ^ Synodus Vicariatus Sutchuensis habita in districtu civitatis Tcong King Tcheou; Anno 1803, Diebus secunda, quinta, et nona Septembris [The Synod of the Vicariate of Sichuan held in the District of the City of Chongqingzhou, in the Year 1803, on the Second, Fifth, and Ninth Days of September] (in Latin). Rome: Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide. 1822. hdl:2027/coo.31924023069010.

- ^ Ma, Te (8 November 2018). "On the Trail of Sichuan's Catholic Past". u.osu.edu. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- ^ Lü 1976, p. 266.

- ^ a b c Tiedemann, R. G. (1 July 2016). Reference Guide to Christian Missionary Societies in China: From the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century. Milton Park: Routledge. ISBN 9781315497310.

- ^ Donnithorne, Audrey G. (29 March 2019). China in Life's Foreground. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 9781925801576.

- ^ "Eglises du silence—Chine : la grande inconnue". sedcontra.fr (in French). 29 April 2011. Archived from the original on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ "Refugee Review Tribunal, Australia" (PDF). unhcr.org. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Wang, Yi (30 August 2007). "基督教在四川的历史要略" [Outline of the History of Protestant Christianity in Sichuan]. observechina.net (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 3 January 2009. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Doyle, G. Wright. "John McCarthy". Biographical Dictionary of Chinese Christianity. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Broomhall 1907, p. 229.

- ^ Baker, Richard T. (1946). Methodism in China: The War Years. New York: Board of Missions and Church Extension. p. 19.

- ^ Gray, G. F. S. (1996). Anglicans in China: A History of the Zhonghua Shenggong Hui (Chung Hua Sheng Kung Huei). New Haven, CT: The Episcopal China Mission History Project. p. 13. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.695.4591.

- ^ Davidson & Mason 1905, p. 154.

- ^ ABFMS 1920, p. 18.

- ^ ABFMS 1920, p. 26.

- ^ Du, Swun Deh (1937). "Quakerism in West China". Bulletin of Friends Historical Association. 26 (2): 88–91. JSTOR 41944051. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Norris, Frank L. (1908). "Chapter X. The Church in Western China". Handbooks of English Church Expansion: China. Oxford: A. R. Mowbray.

- ^ Keen, Rosemary. "Church Missionary Society Archive—Section I: East Asia Missions: Western China". ampltd.co.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2022.

- ^ China Continuation Committee, ed. (1915). 中華基督教會年鑑 [The China Church Year Book] (in Traditional Chinese). Shanghai: The Commercial Press. p. 114.

- ^ Lü 1976, p. 270.

- ^ Yang, Tao (28 December 2013). "四圣祠街:旧时公馆大户扎堆地" [Sishengci Street: An Area for Wealthy Families and Their Mansions]. news.163.com (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Bond 1911, p. 147.

- ^ Austin, Alvyn (1996). "Missions Dream Team". Christian History. Worcester, PA: Christian History Institute. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Zi, Yu (2017). "A Description of CIM Missionary Workers to the Tibetan Highlands Prior to 1950". omf.org. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ Zhu, Yaling (2015). "传教士顾福安及其康藏研究" [The Missionary Robert Cunningham and His Tibetan Studies of the Khams Area] (PDF). 藏学学刊 [Journal of Tibetology] (in Simplified Chinese) (1). Chengdu: Center for Tibetan Studies of Sichuan University: 192. Retrieved 10 June 2021.

- ^ "West China Union University". library.vicu.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "West China Union University" (PDF). divinity-adhoc.library.yale.edu. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Stauffer 1922, p. 231.

- ^ a b Hook, Milton (2020). "Szechwan Mission (1917–1919)" (PDF). encyclopedia.adventist.org. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Hook, Milton (28 November 2021). "East Szechwan Mission (1919–1951)". encyclopedia.adventist.org. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Hook, Milton (28 November 2021). "West Szechwan Mission (1919–1951)". encyclopedia.adventist.org. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- ^ Stauffer 1922, p. 222.

- ^ Dai, Yuetan (28 September 2016). "重庆市万州区基督教圣十字堂的百年历史" [A Centenary History of the Holy Cross Church in Wanzhou District, Chongqing]. gospeltimes.cn (in Simplified Chinese). Archived from the original on 2 June 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ Yang, Tianhong (2010). "中华基督教会在川、康边地的宗教活动" [The Religious Activities of the Church of Christ in China in the Sichuan-Xikang Border Region] (PDF). Historical Research (in Simplified Chinese) (3): 165–182. ISSN 0459-1909. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Chen, Jianming; Liu, Jiafeng, eds. (2008). "Christianity in Sichuan". omf.org. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Ferris, Helen (1956). The Christian Church in Communist China, to 1952. Montgomery, AL: Air Force Personnel and Training Research Center. p. 8. OCLC 5542137.

- ^ Moody, Peter R. (2013). "The Catholic Church in China Today: The Limitations of Autonomy and Enculturation". Journal of Church and State. 55 (3): 403–431. doi:10.1093/jcs/css049. JSTOR 23922765. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Lifton, Robert J. (1957). "Chinese Communist 'Thought Reform': Confession and Re-Education of Western Civilians". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 33 (9): 626–644. PMC 1806208. PMID 19312633.

- ^ "La Chine libère le leader religieux Wusiman Yiming". dohi-pei.org (in French). 24 November 2009. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2022.

- ^ Berlinger, Joshua (17 December 2018). "Detention of 100 Christians raises concerns about religious crackdown in China". edition.cnn.com. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Zaimov, Stoyan (19 November 2018). "Christian churches facing ultimatum in China's Sichuan: Join Communist network or be shut down". christianpost.com. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Courageous Chinese Christians 'Meet in Secret' After Sichuan Three-Self Church Shutdown". barnabasfund.org. 12 March 2020. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "Chinese police raid Christian gathering, arrest one". ucanews.com. 17 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Sanchez, Genesis (2 July 2017). "Our Chinese Orthodox Church: Our Little Chengdu Community". prezi.com. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ Tkacheva, Anna (22 June 2019). "A Refugee from Buddha". orthochristian.com. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

Journal articles

[edit]- Donnithorne, V. H. (1933–1934). Kilborn, L. G. (ed.). "The Golden Age and the Dark Age in Hanchow, Szechwan". Journal of the West China Border Research Society. VI.

- Lü, Shih-chiang (1976). "晚淸時期基督敎在四川省的傳敎活動及川人的反應(1860–1911)" [The Evangelization of Sichuan Province in the Late Qing Period and the Responses of the Sichuanese People (1860–1911)]. History Journal of the National Taiwan Normal University (in Traditional Chinese). Taipei: National Taiwan Normal University Department of History. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

Bibliography

[edit]- Missionary Cameralogs: West China. New York: American Baptist Foreign Mission Society. 1920.

- Bays, Daniel H. (2012). A New History of Christianity in China. Chichester, West Sussex; Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 9781405159548.

- Bond, Geo. J. (1911). Our Share in China and What We Are Doing with It. Toronto: Missionary Society of the Methodist Church.

- Broomhall, Marshall, ed. (1907). "The Province of Szechwan". The Chinese Empire: A General & Missionary Survey. London: Morgan & Scott.

- Davidson, Robert J.; Mason, Isaac (1905). Life in West China: Described by Two Residents in the Province of Sz-chwan. London: Headley Brothers.

- Entenmann, Robert E. (1996). "Christian Virgins in Eighteenth-century Sichuan". In Bays, Daniel (ed.). Christianity in China. Stanford University Press. pp. 180–193.

- Gourdon, François-Marie-Joseph, ed. (1981) [1918]. 圣教入川记 [An Account of the Entry of the Catholic Religion into Sichuan] (PDF) (in Simplified Chinese). Chengdu: Sichuan People's Publishing House.

- Li, Tang; Winkler, Dietmar W., eds. (2016). Winds of Jingjiao: Studies on Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. "orientalia – patristica – oecumenica" series (vol. 9). Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 9783643907547.

- Stauffer, Milton T., ed. (1922). "The Province of Szechwan". The Christian Occupation of China. Shanghai: China Continuation Committee.